Shrines

THE CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION, Durango, Durango, Mexico

A MEXICAN MARTYR: ST. MATEO CORREA

Recently, the head of France’s Bishops’ Conference, Archbishop de Moulins-Beaufort, said that the Seal of Confession should not take precedence over French law (dealing with sex crimes against children). This scandalous statement was the exact opposite of what he had said earlier. What made him change his mind? Well, could it be because he had been summoned for a meeting by the Interior Minister, Gerald Darminin? Could that have something to do with it? It was after this meeting that he reversed his initial position of non-compliance with the government mandate. Even more scandalous, he asked the public to forgive him for his prior statement! This, from the top bishop in France, the “eldest daughter of the Church.”

According to Canon Law and the Catechism of the Catholic Church the Seal of Confession is inviolable. “A confessor who directly violates the Seal of  Confession incurs an automatic excommunication.”

Confession incurs an automatic excommunication.”

This is light years away from another priest, from another time, from another country, who was faced with a similar challenge: Father Mateo Correa. A Mexican priest who literally gave up his life to protect the Seal of Confession. On Feb. 5, 1927, the country’s revolutionary forces ordered the imprisoned priest to divulge the contents of several soldiers’ confessions. “Never! I will never do it!” he said. “I would rather die than violate the Seal of Confession.” “Then you will die!” shrieked his adversary, with a gun pointed at the priest’s head. The next day, at dawn on Feb. 6, 1927, he was taken to the outskirts of Durango and executed. He was canonized by St. John Paul II in 2000.

The years 1926 to 1929 are known as the “Years of the Martyrs” in the history of the Mexican Republic. In the words of English writer Graham Greene (he was an atheist until he converted to the Catholic faith at age 22) the church in Mexico under its socialist dictators suffered “the fiercest persecution of religion anywhere since the reign of Elizabeth.” Pope Pius XI, who presided over the Church from 1922 to 1939, declared that the persecutions in Mexico “exceeded the most bloody persecutions of the Roman emperors.” His 1926 encyclical, Iniquis Afflictisque, refers to the barbarities as “without equal, cruelties and atrocities scarcely credible in the 20th century.”

A priest was not allowed to say Mass, give absolution or even say a prayer over a dying Mexican soldier. Such acts were punishable by law. Father Mateo was arrested because he was bringing Viaticum to a dying invalid; Masses, however, were being said. In secret. In private homes. In forests. In garages. The Church in Mexico was forced to go “underground.” Such a scene is vividly portrayed in Graham Greene’s masterpiece novel, The Power and the Glory:

“It had been five years since the people had seen a priest.

A voice whispered urgently to him, ‘Father.’

‘Yes?’

‘The police are on the way. They are only a mile off, coming through the forest.’

This was what he was used to: were they on horseback or on foot? If they were on foot he had 20 minutes left to finish Mass and hide—the Consecration was in silence: no bell rang.

Somebody opened the door: a voice whispered urgently, ‘They’re here—They are all around the village.’ “

Somebody opened the door: a voice whispered urgently, ‘They’re here—They are all around the village.’ “

The priest was arrested and shot by a firing squad.

Father Mateo Correa was born in Tepechitlan, Zacatecas, on July 23, 1866. Although he was from a poor family, he completed his education with the aid of benefactors and attended the seminary in Zacatecas on a scholarship. After his ordination in 1893 the gentle priest served as pastor in several locations in the state of Zacatecas. One of these was in the mining town of Concepcion del Oro where he became friends with the family of Miguel Pro whose father was a mining engineer. Miguel would eventually become the best-known of all the Mexican martyrs. Father Mateo administered First Communion to the young Miguel and baptized Miguel’s brother Umberto. Both brothers would be martyred on the same day in 1927. As Robert Royal said in his book, The Catholic Martyrs of the Twentieth Century, such ironies are “indicative of the all-embracing nature of anti-Catholic persecution in Mexico.”

The remains of Father Mateo can be found in the Cathedral of Durango, a city 600 miles northwest of Mexico City. The church is also known as the Minor Basilica of the Immaculate Conception. This “landmark of enduring beauty” is located in the historic centre of the city opposite the Plaza de Armas. Construction on the impressive church with its twin-towered Baroque façade was begun in 1695.

Durango is not only a destination for devout Catholics but for fans of John Wayne as well. Many of Hollywood’s greatest western movies were filmed there. As one writer said, “This is John Wayne country, where the Duke slugged it out, shot it out, and sometimes yelled it out, as he tamed the American West.” One of his most famous movies, True Grit, for which he won an Oscar in 1970, was filmed in Durango. Wayne spent a great deal of time in this city and eventually bought property in the area.

“The Duke” converted to the Catholic faith two days before he died of cancer in 1979. According to his grandson, Father Matthew Munoz, a priest in California, he regretted that he had taken so long to take this step. He blamed it on a “busy life.” All of his seven children were brought up in the Catholic faith and attended Catholic schools. Apparently, he had a life-long reverence for Catholicism. His director John Ford (who didn’t hide his love for his Catholic faith) influenced him, as did his good friend in Los Angeles, Archbishop Tomas Clavel, who had been exiled from his Archdiocese of Panama in 1968.

And one can just wonder at the possible influence of Father Mateo Correa on this movie legend. Surely, Wayne, given his interest in Catholicism, would have visited this beautiful Cathedral many times. And how moved he must have been by reading the description in the church of Father Mateo’s martyrdom.

Some of Wayne’s most memorable quotes dealt with the subject of courage. One of his best-known was: “Courage is being scared to death—and saddling up anyway.” How in awe he must have been by Father Mateo’s bravery!

One can only barely surmise the terror in Father Mateo’s heart on that night of Feb. 5, 1927. Alone in his prison cell he had no illusions about any such fictions as a last-minute reprieve. How easily he could have “given in”! Knowing what possible tortures and brutalities awaited him.

Yet he stayed the course. To the point of martyrdom.

Unlike another priest, an Archbishop at that, decades later, who did “give in.” To the Interior Minister’s admonitions. Or threats. Or whatever it was. To which one can only say, “God help the Church in France.”

Saint Mateo Correa, pray for the Church!

THIS ARTICLE WAS REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM One Peter Five.

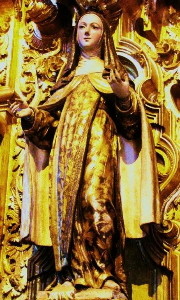

OUR LADY OF THE PILLAR, La Ensenanza Church, Mexico City

Step into the church of La Ensenanza in the historical district of Mexico City and you will be entering what many writers refer to as one of the most beautiful churches in the country. Its façade is outstanding as well.

Step into the church of La Ensenanza in the historical district of Mexico City and you will be entering what many writers refer to as one of the most beautiful churches in the country. Its façade is outstanding as well.

The architecture of La Ensenanza is known as Churrigueresque, a type of ultra-Baroque construction that is named after the Spanish architect, Jose Churriguera, who dominated Spanish architecture for the first half of the 18th century. As is evident by the photos on this website, this style of architecture is characterized by an extravagance of sculptural details, or, to quote one author, “a plethora of elaborate decoration.” Gilded carvings, rosettes, sculpted clouds and angels, paintings and statues, adorn all surfaces in splendid array. All with one mystical purpose: to give glory and praise to God with all one’s heart and soul. It is a style of architecture unique to Spain and Latin America, particularly Mexico. The church is quite small (I doubt if it could hold even 100 people) and is a five-minute walk to the zocalo (central square of the city).

The church of La Ensenanza was named for the convent of the same name which was founded by one of the most distinguished women in 18th century Mexico: Mother Maria Ignacia de Azlor y Echevers. Her primary goal was to provide quality education for the girls and women of the city, a project to which she dedicated her life. She died in 1767 and the construction of the church was begun a few years later. By 1778 the church was completed and was consecrated by Archbishop don Alonso Nunez de Haro y Peralta. The expulsion of the religious in 1861 by the edicts of the revolutionary government resulted in the abandonment of the convent. The church, however, was conserved.

The Virgin of the Pillar is the central figure above the main altar. She is holding the Child Jesus and is standing on a column which is typically obscured by a mantle (in this case a brightly coloured green fabric). Can you see the column below the mantle in the photograph?

The Virgin of the Pillar is the central figure above the main altar. She is holding the Child Jesus and is standing on a column which is typically obscured by a mantle (in this case a brightly coloured green fabric). Can you see the column below the mantle in the photograph?

But what was the origin of the name, “The Lady of the Pillar?” Tradition relates that Our Lady appeared to the apostle St. James in 40 AD in Zaragoza, Spain. Apparently he was having many trials in his preaching and was getting discouraged with his lack of progress. She came to encourage him and offer him strength! She was accompanied by a myriad of angels who carried a column of marble and a small statue of Our Lady on top of the column.

She asked that St. James have a temple built in the area of the apparition. It is considered the first apparition of Our Lady in history. In 1730 Pope Innocent XIII authorized veneration of Our Lady of the Pillar throughout the Spanish Empire (including Mexico and Latin America). The Spanish mystic, Venerable Mary of Agreda, described the happenings in her book, THE MYSTICAL CITY OF GOD. The feast day of Our Lady of the Pillar is October 12.

OUR LADY OF THE ANGELS, Tecaxic (Toluca) State of Mexico

Our Lady of Guadalupe is the iconic image of Mexico. You see her image everywhere. On billboards, on store-fronts, on buses, in taxis. There is a statue or painting of her in every church in the country and a multitude of churches dedicated to her throughout Mexico.

But did you know that there is another miraculous image of Our Lady in Mexico that closely resembles her? It is the image known as Our Lady of the Angels, found in Texacic, a small town 2 km. distance from the city of Toluca, the capital city of the state of Mexico (64 km west of Mexico City).

Like the painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe, this ancient image of Our Lady of the Angels is painted on a tilma, a cloak made of a fabric similar to cotton. Like Our Lady of Guadalupe, Our Lady of the Angels assumes the same posture with her hands joined in prayer. And can you see the golden rays which burst forth behind her? For a moment you almost think you are looking at a painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe! Two angels hold up Our Lady of the Angel’s mantle as she is lifted up to heaven ( this is an image of Our Lady of the Assumption).

In the early history of the painting we discover that Tecaxic was once a thriving pueblo with a vibrant Catholic faith, thanks to the preaching of the Franciscans who journeyed from their monastery in Toluca. The plague of 1640, however, devastated Tecaxic and the town was ultimately abandoned.

In the early history of the painting we discover that Tecaxic was once a thriving pueblo with a vibrant Catholic faith, thanks to the preaching of the Franciscans who journeyed from their monastery in Toluca. The plague of 1640, however, devastated Tecaxic and the town was ultimately abandoned.

Also abandoned was the painting of Our Lady of the Angels, which had been displayed on the walls of a tiny hermitage in the town. Over time the hermitage became a total ruin. The roof broke down and enormous holes appeared in the walls. The painting was left exposed to the mercy of the elements “pummeled by rains, dust and scorched by a glaring sun.”

Despite the attacks of the weather throughout the years, the painting remained intact and the colours remained fresh and vivid. Its preservation is remarkable considering that it was painted on a fabric that should have disintegrated within a few years. After its removal to a new shrine, the miraculous nature of the painting was officially established in 1684 by Fray Baltazara de Medina, Censor for the Holy Office of the Inquisition.

Many are the miracles associated with the 300-year-old painting of Our Lady of the Angels: the cure of a cancerous arm that was to be amputated, sight restored to a blind man and the healing of a crippled woman are just some of the cures attributed to Our Lady of the Angels. The reports of all these miracles prompted Fray Jose Gutierrez, the Guardian of the Convent of San Francisco in Toluca, to begin the building of a new sanctuary in her honour in 1650.

Miracles of another kind were also witnessed in the new sanctuary: mysterious singing and the emanation of lights! Reports were told of hearing music of “remarkable beauty” from the shrine. When investigators entered the church, however, they witnessed only silence and solitude. Similar reports were told of seeing flickering lights emanating from the shrine. When passersby investigated they found only darkness. No one was present in the shrine!

Miracles of another kind were also witnessed in the new sanctuary: mysterious singing and the emanation of lights! Reports were told of hearing music of “remarkable beauty” from the shrine. When investigators entered the church, however, they witnessed only silence and solitude. Similar reports were told of seeing flickering lights emanating from the shrine. When passersby investigated they found only darkness. No one was present in the shrine!

Today Our Lady of the Angels in Tecaxic is a thriving parish church. And fervent devotion to her has been ongoing for almost four centuries!

One detail from the painting should not be missed: noticeable is that Our Lady’s left ear is exposed, (it is not covered by her dark hair) indicating that Our Lady is most willing to listen attentively to the sorrows and joys of all of her children who implore her intercession.

OUR LADY OF LIGHT, Leon, Guanajuato

Shoes. Shoes. Shoes. And more shoes! That’s what you’ll find in Leon in exuberant abundance. Leon, the fifth largest city in Mexico, in the central state of Guanajuato, is known as the shoe capital of the country. That is one of its two claims to fame. Leon has not just one mall devoted exclusively to shoes, nor even two or three. It has four malls which sell nothing but shoes. Hiking boots. Sandals. Golf shoes. Ballet shoes. Tennis shoes. Oxfords. And cowboy boots. Particularly cowboy boots. In every colour of the rainbow. From canary yellow to aquamarine. One display featured an assortment of different cowboy boots—all in Hunter green—of all colours. These malls are all grouped together in one location—conveniently (and cleverly!)—right beside the bus station. You can see them as soon as you get off the bus.

Shoes. Shoes. Shoes. And more shoes! That’s what you’ll find in Leon in exuberant abundance. Leon, the fifth largest city in Mexico, in the central state of Guanajuato, is known as the shoe capital of the country. That is one of its two claims to fame. Leon has not just one mall devoted exclusively to shoes, nor even two or three. It has four malls which sell nothing but shoes. Hiking boots. Sandals. Golf shoes. Ballet shoes. Tennis shoes. Oxfords. And cowboy boots. Particularly cowboy boots. In every colour of the rainbow. From canary yellow to aquamarine. One display featured an assortment of different cowboy boots—all in Hunter green—of all colours. These malls are all grouped together in one location—conveniently (and cleverly!)—right beside the bus station. You can see them as soon as you get off the bus.

But as popular as they are, the shoe malls are not the main source of pride for the citizens of Leon. The real treasure of the city is a remarkable painting just a few blocks away: the miraculous painting of Our Lady of Light which is displayed over the main altar of the city’s elegant cathedral, a church that was begun by the Jesuits in 1746.

Our Lady of Light (La Luz) was named the chief Patrona of the city of Leon in 1849. When Leon was declared a diocese in 1872 Our Lady of Light was named its Patrona as well. Approval of the authenticity of the painting’s origins came from the highest levels of the church: The painting was crowned in 1902 with the authorization of Pope Leo XIII.

She is known for her miraculous powers of intercession. One of these occurred in a spectacularly public manner on June 18, 1876. The cathedral was packed that Sunday morning for the 11 am Mass. Suddenly, without warning, a loud crack reverberated throughout the entire church. To everyone’s horror “the keystone of the main arch, a tremendous block of masonry, fell into the aisle.” It looked as if the entire ceiling would crash down killing everyone below. The congregants froze in terror.

At this terrible moment, Bishop de Sollano, with supreme presence of mind and faith, walked down from the altar and stood under the arch. The congregation held its collective breath. He prayed urgently to Our Lady of Light to support the arch so that all would be protected. His prayers were heard. Miraculously, not a single person in the church was injured. They are still talking about it in Leon to the present day!

The painting originated in Europe: It all began with a Jesuit priest, Father Giovanni Antonio Genovesi, who was born in Sicily in 1684. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1703 and spent the next twenty years as a missionary priest, “traversing the length and breadth of Sicily.” He was becoming disheartened, however, because so few people were converting. Father Genovesi, who had a great love for the Blessed Mother, had an inspiration: “I need an image of Our Lady to carry with me,” he said, “one that will convert sinners and move hearts!” She will do it! He was sure of it! But what image? And where would he find such a one?

He had heard that a holy nun in Palermo was receiving visitations from Our Lady. “I will ask her!” he said. “And she can ask the Blessed Virgin what she herself would like!” Father Genovesi travelled to Palermo to meet with the nun. The year was 1722. The nun thought this was an excellent idea and proceeded to ask Our Lady this very question. Before long, Our Lady appeared to her in a splendour of light surrounded by a “courtege of angels.” She was holding the Infant Jesus in one arm and with the other arm, she was snatching a sinner from the jaws of a demon. An angel knelt before her holding a basket of human hearts; The Infant took them “one by one, sanctifying them with His hands.”

Our Lady then spoke, repeating the command twice: “I wish the painting to be as you have seen me,” she said. “The title of the painting should be known as the Most Holy Mother of Light.” The nun immediately passed on the message to Father Genovesi who commissioned an artist to carry out Our Lady’s wishes.

No matter how many times the artist tried, however, he was not able to match the nun’s description of the sacred scene. Time and time again this happened. “No, it was nothing like that!” said the nun. Apparently, not even the Blessed Mother was happy with the painting!

Our Lady appeared yet again to the nun: “What are you doing here, Lazybones?” she said to the nun who lived a fair distance from Palermo, “when I need you in Palermo for a matter which concerns my glory?”

Our Lady told the nun to meet her at the artist’s studio and that she, herself, would guide the artist’s brush-strokes! Our Lady would be visible only to the nun. “When the work is done,” said the Virgin, “all shall know by its more than human beauty that a greater mind and a higher art have arranged the composition and laid the colors.”

Our Lady was delighted with the finished painting; it became known as Our Most Holy Mother of Light. She raised her hand to the completed work and blessed it with the Sign of the Cross.

Father Genovesi carried the painting with him on his missionary journeys; wherever he went conversions multiplied exponentially. “Our Lady moved the hearts of all sinners!” he said. “The Virgin worked marvels through her image,” reported one historian. And devotion to Our Lady of Light spread throughout all of Sicily.

But how did the painting end up in Mexico?

It happened like this: Another Jesuit from Sicily, Father Jose maria Genovese (with almost the same surname as the original Father Genovesi), had arrived in Mexico in 1707. News spread about the miraculous painting of Our Lady of Light and Father Genovese began erecting altars to her in Mexico. Devotion to her flourished just as it did in Sicily. The Jesuits decided that the painting should be sent to one of their many churches in New Spain (Mexico). But to which church? Where? In which city?

They agreed that the selection would be made by casting lots: The choice? The Jesuit church in Leon. A second, then a third drawing, confirmed the first. Leon it would be!

On July 2, 1732 the miraculous painting of Our Lady of Light arrived in the city of Leon amid crowds, “triumph,” and “indescribable enthusiasm.” Every year on the second of July, to the present day, the people of Leon commemorate the event with a joy-filled lively fiesta.

A statement written on the back of the painting testifies to its authenticity: “This image is the original which came from Sicily and which was blessed by the same Virgin, who with her blessing, entrusted it with the power to do miracles.” It is dated August 19, 1729 and is signed by a number of Sicilian Jesuit priests.

Since then Our Lady of Light has become known for her outstanding powers of protection for the people of Leon: She has saved them from epidemics, storms, lightning, and plagues. Even revolutions! Leon is known as the “City of Refuge” because it enjoyed serene peace during the many revolutions and invasions that have beset the rest of Mexico for almost two centuries.

Although she is celebrated throughout the republic of Mexico (you can see her image in many churches in the country) she is especially revered in Leon. You will see her image everywhere in the city: in cars, churches, coffee shops, billboards, and city buildings. Taxi drivers and bus drivers erect tiny shrines to her on their dashboards, complete with flashing, sparkling lights. Parents name their daughters after her. The two most common girls’ names in Leon are Guadalupe and Luz (after Our Lady of Light).

It is said that Leon is the city of Mary. The sumptuous cathedral is the centre of the religious life of the city. And at its heart is the miraculous image of Our Lady of Light.

And the shoe malls? They run a distant second. A very distant second.

.

CATHEDRAL OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION, Xalapa, Veracruz: SAN RAFAEL GUIZAR VALENCIA

The remains of San Rafael Guizar Valencia (1877-1937) lie in state in the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, in Xalapa, Veracruz, the capital of the state. During his life he had been imprisoned, hunted down, and driven into exile. He was shot at five times. You might wonder with such a past:

Was he once a gangster? A ne-er do well? A criminal of the worst kind? Who perhaps experienced a dramatic conversion in his life?

He was none of these things. He was—of all things—a bishop! And not just any bishop. He was the first bishop to be canonized a saint who was born on American soil.

He lived during the brutal years of the anti-Catholic persecution in Mexico during the 1920’s. A time described by British author Graham Greene as “the fiercest persecution of religion anywhere since the reign of Elizabeth.” Thousands of Mexican Catholics died defending their faith during this era. Pope Pius X declared that this period “exceeded the most bloody persecutions of the Roman emperors.” The US ambassador, James Sheffield, spoke about Plutarco Calles, who was president of Mexico during the worst days of the persecution. “He is so violent on the religion question that he has lost dominion of himself—his face burns and he hits the table to express his deep hatred of religion.”

He lived during the brutal years of the anti-Catholic persecution in Mexico during the 1920’s. A time described by British author Graham Greene as “the fiercest persecution of religion anywhere since the reign of Elizabeth.” Thousands of Mexican Catholics died defending their faith during this era. Pope Pius X declared that this period “exceeded the most bloody persecutions of the Roman emperors.” The US ambassador, James Sheffield, spoke about Plutarco Calles, who was president of Mexico during the worst days of the persecution. “He is so violent on the religion question that he has lost dominion of himself—his face burns and he hits the table to express his deep hatred of religion.”

“His apostolate was carried out among constant danger and persecution” said Pope John Paul II during the homily for Bishop Valencia’s beatification in 1995. Bishop Valencia, disguised as a junk-dealer (priests could be arrested or killed on the spot) risked his life numerous times to administer the Sacraments to dying soldiers on the battlefield “as the bullets whistled by.” His courage was legendary. “I want to give my life for the salvation of souls,” he said repeatedly.

He was born into a wealthy ranching family in the central Mexican state of Michoacan, the fourth of eleven children. He lost his mother when he was nine years old. Her death left a huge vacuum in the young boy’s life. After her funeral he knelt before a statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe and declared, “Now you will be my mother and companion on earth” much as did St. Therese of Lisieux, under the same circumstances, several years before. This devotion to the Blessed Mother, as well as to the Eucharist, stayed with him for the remainder of his life. He composed several Marian hymns which are still sung today throughout the state of Veracruz.

Two years after his ordination in 1901, he founded a congregation of missionaries named in honour of Our Lady of Esperanza (“Hope”) much venerated in that part of Mexico. This image has the distinction of being the first image of Mary to be crowned in the Americas. A photo of this image of Our Lady is found on this website page. For an article on OUR LADY OF ESPERANZA please see the website page for May 2020.

Two years after his ordination in 1901, he founded a congregation of missionaries named in honour of Our Lady of Esperanza (“Hope”) much venerated in that part of Mexico. This image has the distinction of being the first image of Mary to be crowned in the Americas. A photo of this image of Our Lady is found on this website page. For an article on OUR LADY OF ESPERANZA please see the website page for May 2020.

He had a “holy obsession” with giving missions. In the city of Zamora (population: 12,000) 7,000 people attended “The Great Mission of Zamora” in 1904. The whole city was touched by his preaching and he became known as the “mover of hearts.” And, for each mission, his accordion accompanied him: “music and evangelization are inseparable” he always said.

During his years of exile in Cuba, Guatemala and Texas, he preached countless missions. In Guatemala, “greatly indifferent to religion” it was reported that “the people converted in an explosion!” In Cuba he gave a mission to 1,200 prisoners, most of whom had lived a “violent and turbulent life.” At the end of the week all but twelve went to confession, many reduced to tears. Called a “magnet for souls” the kindly and humble bishop was able to penetrate the “hardest of hearts.”

Catechesis (the catechism he wrote is still in use in the state of Veracruz today) and the formation of priests remained his priorities during his lifetime. He considered his seminaries “the apple of his eye.” He opened a seminary in Xalapa, Veracruz in 1920 but this was closed down by the anti-Catholic government. He moved his seminary to Mexico City in 1922 and during the height of the persecution his underground seminary had 300 seminarians! It continued to operate for 15 more years.

Bishop Valencia has often been compared to St. John Bosco (1815-1888) of whom Pope XI said, “the supernatural almost became natural and the extraordinary, ordinary.” Among many mystical phenomena associated with St. John Bosco was the miraculous multiplication of food for his impoverished school-boys. Like this saint, Bishop Valencia also experienced the multiplication of food and bienes (goods) for all of the poor he assisted in his lifetime.

Bishop Valencia has often been compared to St. John Bosco (1815-1888) of whom Pope XI said, “the supernatural almost became natural and the extraordinary, ordinary.” Among many mystical phenomena associated with St. John Bosco was the miraculous multiplication of food for his impoverished school-boys. Like this saint, Bishop Valencia also experienced the multiplication of food and bienes (goods) for all of the poor he assisted in his lifetime.

Most astonishing, though, was his experience of levitation, a state in which “one’s body is lifted in the air with no apparent physical assistance.” Several anciones (elderly people) interviewed for his cause of canonization, testified that they were eyewitnesses to this phenomena while he was saying Mass. St. Teresa of Avila described the experience: “It seemed that I was lifted up by a force beneath my feet that was so powerful that I knew nothing to which I can compare it for it came with a much greater vehemence than any other spiritual experience.” Doctor of the Church, St. Alphonsus Ligouri, and Pope Celestine V, as well as 200 other saints and holy people, also experienced levitation.

In 1950 his body was found incorrupt, twelve years after his death (he died of natural causes). He was known as “the bishop of the poor.” He gave away all of his inherited wealth to build schools, orphanages, and seminaries. He lived frugally and gave away everything he had to the poor.

At his death “a river of light which never ended”—thousands of mourners with lit candles—filed by his casket all night long. “A halo surrounded him all his life” said one mourner.

OUR LADY OF THE LONELY, Oaxaca, Oaxaca (La Soledad)

There is one business that is thriving in this pandemic: The dog-breeding business. Of all things!

There is one business that is thriving in this pandemic: The dog-breeding business. Of all things!

This I did not know. I discovered this one day as I was walking along the pier at our lake-side city. A popular spot with dog-walkers. Of which we have a great many in our town. As I struck up a conversation with one dog owner, another couple came along admiring this fellow’s pooch. They wanted one just like it but couldn’t afford it. “The prices have doubled, maybe even tripled since the pandemic began. The prices have gone through the roof!” they lamented. This was news to me.

When I got home I decided to look the subject up on the Internet. And sure enough, this was the case: Barry Harrison, of London, Ontario, a dog-breeder for over thirty years, said “People are scrambling to buy any type of puppy.” He has never fielded so many calls. “Breeders are incredibly overwhelmed with all the inquiries they’re getting,” he said. He cited the main reason as loneliness. “With the pandemic people are incredibly lonely and cut off from social contact. They buy a dog to have company.”

On the subject of loneliness, the people of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, know a thing or tow about dealing with such trials, albeit on an exalted plane, a heavenly one to be exact. They have their special protector, Our Lady of the Lonely, LA SOLEDADE who is the Patrona and protector of their state. She has been looking after her citizens of Oaxaca for over four hundred years. And consoling them when they are feeling lonely and bereft. Many believe that she has supernatural healing powers as well.

Travel writers rave over the city of Oaxaca and rightly so. They call it “a rare beauty, a wonder to behold.” It is no surprise that this elegant city has become a major tourist destination. It is nestled in a valley in the Sierra Madre del Sur mountains and boasts an “ideal climate.” Its zocalo—with its sprawling jacaranda trees and outdoor cafes—is the centre of the city’s social life where visitors can enjoy live music almost every night of the week.

Because her original shrine (the chapel of San Sebastian) was too small to hold her ever-increasing devotees, the bishop authorized the construction of a much larger church to house the magnificent image of La Soledad. The Basilica of La Soledad was completed in 1689. One travel guidebook calls it “the most important religious centre in Oaxaca,” quite an accolade in a city with twenty-seven churches!

Because her original shrine (the chapel of San Sebastian) was too small to hold her ever-increasing devotees, the bishop authorized the construction of a much larger church to house the magnificent image of La Soledad. The Basilica of La Soledad was completed in 1689. One travel guidebook calls it “the most important religious centre in Oaxaca,” quite an accolade in a city with twenty-seven churches!

The “outstanding façade” of the church is singularly unique in the country: It is formed almost like a folding screen that “moves” on different planes, a Baroque technique which enlarges the surface available for decoration. Twenty-one sculptures adorn the façade. The beautiful interior of the church is in the neo-classical style and above the main altar resides the magnificent statue of Our Lady of the Lonely. Almost life-size, she is sumptuously adorned in a black velvet robe encrusted with thousands of pearls donated by grateful sailors. She is their special patron, after all! She is reputed to be the richest Madonna in Latin America. And this is in the literal sense: Her crown has two kilos of solid gold and six hundred diamonds! All donated by her devoted Oaxacans.

Many are the honours bestowed on Our Lady of the Lonely from the highest levels of the church:

- In 1909 she was solemnly crowned by the authorization of Pope Pius X.

- The sanctuary was elevated to the category of a Basilica by Pope St. John 23rd in 1959.

- Pope St. John Paul ll visited the shrine in 1979.

And one wonders: What was her history? Where did she come from?

She has a most fascinating background! And one of the most unusual in all of Marian scholarship:

The date was December 17, 1620. The muleteers were rejoicing because they had only one day left before they reached the city of Oaxaca. They had left Veracruz several weeks earlier enroute to their final destination, Guatemala. This last night they were camping in the country under the “open skies and the stars.” They woke up before dawn and loaded the mules in preparation for the last leg of their long journey. It was still dark as they continued on their way.

Suddenly, one of the muleteers shouted out in a panic, “Patron! Patron! One of these mules doesn’t belong to us! It is a strange mule!” The leader went to investigate and sure enough, it was not one of theirs! But whose was it? And where did it come from? No one in the area had ever seen it before. Not only that—its cargo was different too—the mule had a large box on its back. The patron ordered everyone to search the surrounding countryside to find the owner of the lost mule. Search as they might, they could not find its owner! Nor did anyone they encounter know anything about this particular mule. There seemed to be not a trace of him anywhere! By now the muleteers were worried about reaching their destination of Oaxaca in good time. They could look no longer. They would take up the matter with the mayor of Oaxaca once they reached there.

Suddenly, one of the muleteers shouted out in a panic, “Patron! Patron! One of these mules doesn’t belong to us! It is a strange mule!” The leader went to investigate and sure enough, it was not one of theirs! But whose was it? And where did it come from? No one in the area had ever seen it before. Not only that—its cargo was different too—the mule had a large box on its back. The patron ordered everyone to search the surrounding countryside to find the owner of the lost mule. Search as they might, they could not find its owner! Nor did anyone they encounter know anything about this particular mule. There seemed to be not a trace of him anywhere! By now the muleteers were worried about reaching their destination of Oaxaca in good time. They could look no longer. They would take up the matter with the mayor of Oaxaca once they reached there.

Famished and exhausted they finally arrived at Oaxaca at 9 am and rested in front of the chapel of San Sebastian. After a quick meal they planned to depart and resume their march forward.

But that mule, “the strange one,” threw himself in front of the chapel and would not budge. And that was that! They tried to rouse him, prod him, beat him, shove him and shake him. He still would not move.

And yet they couldn’t leave him there! What to do? They were completely frustrated with this stubborn creature! As if things were not bad enough, the mule then shook himself violently, “as if struck by lightning” and fell down dead!

Now, not only would they be accused of stealing the mule, they would be accused of killing him as well! By this point in time, quite a large crowd of curiosity-seekers had gathered round. “They’ll think you killed him!” they said. “You had too heavy a load on him! That’s why he died!” said another. The muleteers were frantic. They were terrified that they would not only be arrested but that they would be put in jail!

At 11 am the mayor and his four employees arrived. They were startled to find a dead mule! No one had yet dared to open up the box on the mule’s back. “Open the box!” declared the mayor in an authoritarian manner.

At 11 am the mayor and his four employees arrived. They were startled to find a dead mule! No one had yet dared to open up the box on the mule’s back. “Open the box!” declared the mayor in an authoritarian manner.

Inside the box they saw an image of Our Lord Jesus Christ and a sign. At the other end of the box, “as though sustained by a mysterious force” they found an image of Our Lady—a beautiful head and delicate hands, exquisitely sculptured as by a “master sculptor from Spain.” The words on the sign, in upper case letters, declared “HOLY MOTHER OF THE LONELY, AT THE FOOT OF THE CROSS.”

The mayor was overcome by emotion and in a shaken voice said: “This is not within my competence, call the priest!” Several of the group immediately ran to get the bishop, Bishop Bartolome de Bohorquez e Hinajosa. When he saw the image of Our Lady he proclaimed, “Milagro! Milagro!” (Miracle! Miracle!). He placed the image of Our Lord in a nearby chapel. Once the statue of Our Lady was fully completed and garbed the bishop ordered that it be situated in a place of honour in the chapel of San Sebastian.

And that is the story of how Our Lady of the Lonely became the Patrona of the state of Oaxaca.

One of Our Lady’s titles is “Our Lady, Comforter of the Afflicted.” She is known for this. It is her specialty. St. Louis de Montfort (1673-1716) speaks prophetically about this very thing in his True Devotion to Mary. He says we are consoled by her in “the crosses, toils and disappointments of life—in the ever-perilous times which are to come.”

And are we not living in such perilous times now?

OUR LADY OF IZAMAL

The Yucatan. To winter-wearied North Americans the name revives images of turquoise seas, powder-white beaches, and ancient Mayan ruins. The Yucatan Peninsula is alleged to have one of the richest stores of archaeological ruins in the world and is home to the Maya Indians, the largest indigenous group in North America. The peninsula is comprised of the three states of Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo.

The Yucatan. To winter-wearied North Americans the name revives images of turquoise seas, powder-white beaches, and ancient Mayan ruins. The Yucatan Peninsula is alleged to have one of the richest stores of archaeological ruins in the world and is home to the Maya Indians, the largest indigenous group in North America. The peninsula is comprised of the three states of Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo.

If tourists can pry themselves away from the beaches, a prime location for the exploration of such ruins would be the town of Izamal, “a jewel of a colonial city” in the heart of the Yucatan Peninsula, 70 miles from Cancun and 45 miles from the state capital, Merida. As fascinating as the ruins, are, however, the “top attraction” of Izamal, according to travel guidebooks, is the “magnificent” Franciscan convent of St. Anthony of Padua which was initiated almost five centuries ago. It was one of the first monasteries in the western hemisphere and became the centre of evangelization for the entire peninsula.

The enormous complex, consisting of church, atrium, and convent, is one of the largest of its kind in America and its atrium (with its seventy-five distinctive arches), is reputed to be the second largest in the world, after St. Peter’s in Rome. The entire edifice is painted a vibrant shade of yellow. The entire town, in fact, is painted in this same colour which is why it is called “The Yellow City” in travel books. “Jewel” indeed! Instead of taxis, the main mode of travel in the town for both locals and tourists are the calesas, the horse-drawn buggies and one notes—the horses, also, are decked out in yellow! And the pleasant metronome-like sound, clippity-clop, clippety-clop, clippity-clop resounds through the tropical town. Cobblestone streets and colonial lampposts complete the idyllic setting.

The convent was built upon the platform of the immense temple, Pap-Hol-Chac, a ceremonial temple dedicated to the Maya pagan god of rain. The town of Izamal had been the headquarters for the worship of the supreme god, Itzamna, and the sun god, Kinich-Kakmo; it had been the centre for the Mayan priesthood as well.

Franciscan friar, Fray Diego de Landa, who founded the convent complex in 1549, was named its guardian in 1553. He became the second bishop of Yucatan in 1572. He chose the site, himself, “in order that a place that had been one of abomination and idolatry could become one of sanctity,” thus making holy a place where human sacrifice and idolatry had once been practiced. The pagan pyramid was demolished and its stones were used for the building of the new monastery, thus signifying the sublime triumph of Christianity over paganism. With his own hands he chopped down the trees and hauled stone for the buildings, working alongside the Maya at every turn.

Franciscan friar, Fray Diego de Landa, who founded the convent complex in 1549, was named its guardian in 1553. He became the second bishop of Yucatan in 1572. He chose the site, himself, “in order that a place that had been one of abomination and idolatry could become one of sanctity,” thus making holy a place where human sacrifice and idolatry had once been practiced. The pagan pyramid was demolished and its stones were used for the building of the new monastery, thus signifying the sublime triumph of Christianity over paganism. With his own hands he chopped down the trees and hauled stone for the buildings, working alongside the Maya at every turn.

At the heart of the monastery is the church dedicated to Our Lady of Izamal, the principal Marian shrine in the Yucatan. Because Izamal had been the headquarters for the Maya priesthood, the Franciscan friars dedicated the area to the Virgin Mary. According to the secular periodical, Yucatan Today, “Izamal’s people are very devoted to the Immaculate Virgin to this day.” As early as 1519, two years before the Spanish Conquest, Cortez landed on the island of Cozumel in Quintana Roo and erected an image of the “Most Pure Virgin” on the site. Fray Diego de Landa recorded that the first Spanish words the Maya of Cozumel learned were “Maria! Maria! Cortez, Cortez!” Even today you can see signs of this devotion: As soon as you get off the bus at Izamal, the first thing you see is a statue of Our Lady of Izamal—right in front of the bus station!

And one has to wonder: What is the origin of this revered statue? In 1588 Fray Landa travelled to Guatemala, the famed New World centre of religious art, to procure an image of the Blessed Virgin for the monastery at Izamal. He had heard legendary reports of an exquisite statue of Our Lady in the Franciscan church in Guatemala, which had been created by the renowned Franciscan sculptor, Fray Juan de Aguirre. He wanted one just like it for his monastery! To Fray Landa’s great delight, Fray Juan was still alive and flourishing, although advanced in years. The sculptor took on the charge with gusto and within a short time, the 46” tall statue, dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, was completed.

And one has to wonder: What is the origin of this revered statue? In 1588 Fray Landa travelled to Guatemala, the famed New World centre of religious art, to procure an image of the Blessed Virgin for the monastery at Izamal. He had heard legendary reports of an exquisite statue of Our Lady in the Franciscan church in Guatemala, which had been created by the renowned Franciscan sculptor, Fray Juan de Aguirre. He wanted one just like it for his monastery! To Fray Landa’s great delight, Fray Juan was still alive and flourishing, although advanced in years. The sculptor took on the charge with gusto and within a short time, the 46” tall statue, dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, was completed.

The return journey from Guatemala began to manifest Our Lady’s special predeliction for her children of the Yucatan: as the caravan processed through the town of Vallodid a group of Spaniards—struck by the beauty of the statue—demanded that the statue be retained in their town. “It’s too lovely to be relegated to an Indian pueblo!” they decided. “Hand it over!” they bellowed. The Maya refused. At this juncture in the debate a group of the sturdiest of the Spanish men amassed together and said, “Move over! It’s ours now!” And then a miracle happened: The box containing the statue refused to budge! It became so impossibly heavy that twelve men could not lift it an inch off the ground. After much exertion and humiliation, the Spaniards realized that Our Lady’s intention was to remain with her beloved Maya people. Historians recounted another miracle on this journey: Although it rained frequently on the trip “the area about the bearers and their cargo always remained dry.” And in this way the group continued blissfully on its way to Izamal—

Perhaps the greatest miracles associated with Our Lady of Izamal occurred in the ensuing years, miracles which are most pertinent to us now as we face the Covid-19 plague. The Yucatan had its share of lethal plagues: In August 1648 a great epidemic, “a horrible peste” roared across the Yucatan peninsula. In this crisis the Maya turned to Our Lady of Izamal, consecrating the province to her as their special patroness “against epidemics, illnesses and public calamities.” That the plague abated quickly was attributed to the direct intercession of Our Lady.

Toward the end of the 17th century “another plague raged so fiercely that it was feared that the town of Campeche would have to be abandoned.” Those who were able, fled to Merida, which “within a month was one vast hospital of dead and dying.” In this “extremity” the Meridians begged the Franciscan Provincial to bring the statue of Our Lady of Izamal to the capital for a solemn novena of prayer. In a short time the plague disappeared from the city. A similar plague struck the city again in 1730 and once again Our Lady of Izamal came to their aid.

Toward the end of the 17th century “another plague raged so fiercely that it was feared that the town of Campeche would have to be abandoned.” Those who were able, fled to Merida, which “within a month was one vast hospital of dead and dying.” In this “extremity” the Meridians begged the Franciscan Provincial to bring the statue of Our Lady of Izamal to the capital for a solemn novena of prayer. In a short time the plague disappeared from the city. A similar plague struck the city again in 1730 and once again Our Lady of Izamal came to their aid.

Many honours have been bestowed on Our Lady of Izamal: in 1949 she was not only crowned by the authorization of Pope Pius Xll but she was also declared the Reina, the Queen of the Yucatan. In 1970 she was named the Patrona of the Archdiocese. Her greatest honour came when St. Pope John Paul ll visited her shrine in 1993 and crowned her a second time. She may be the only statue in the western world to be crowned twice. By the authorization of two pontiffs!

As the Covid-19 plague envelops the world, let us turn to Our Lady of Izamal. She is experienced in these matters. And will know exactly what to do.

This article has been reprinted with permission from ONE PETER FIVE.

LA PIEDAD: MEXICO CITY

The painting above the main altar of the church of La Piedad has the most intriguing history—

The story of the

Dominican convent of La Piedad dates back to 1595. The friars wanted a painting of Our Lady for their new convent so they sent a friar and a laybrother to Rome to commission an image of Our Lady holding her Crucified Son. Once in Rome, the two found a renowned painter who agreed to their terms; however, he couldn’t give them a completion date. “We have to return to Mexico in a month,” they told him. He merely shrugged. In fact, he didn’t seem particularly interested in the project at all!

When they went to collect the painting a month later the artist handed them a black and white sketch. “That’s the best I can do!” he said. “But we’re leaving tomorrow!” cried the friar. “Well, that’s too bad,” said the artist, none too concerned.

The heavy-hearted Mexicans had no choice. They carefully packed the “painting” in a wooden crate for the long journey home. During the voyage a fierce storm engulfed the ship. “Padre! We’ll all be drowned!” they shrieked.in terror. “Have confidence in Our Lady, Star of the Sea,” answered the priest. “She can calm the waters in a glance.” All on board prayed fervently to Our Lady of Piedad to save their lives. Sure enough, the sea became calm and the pair arrrived safely in Veracruz. As they travelled overland to Mexico City they became increasingly uneasy. “How disappointed they all will be!” murmured the friar.

After warmly welcoming the travellers home, the friars were anxious to see the painting. “Open the crate!” they shouted. “Let’s see the painting!” When they removed the wrappings from the container—the sketch was no longer a sketch! Instead, in its place, was a full-colour painting of immense beauty. Full of wonder, the amazed pair knelt before the painting and recounted the extraordinary tale.

The miraculous oil painting has been venerated for four centuries up to the present day where it hangs above the main altar of the church of La Piedad in central Mexico City. Its size is immense: 9 ft.(3m) in height by 8 ft.(2.5m) in width. The colours today are as vivid and bright as if they had been painted yesterday.

Countless miracles have been enacted through her intercession and many of these have been verified by formal ecclesiastical investigation. Numerous indulgences have been authorized to the church of La Piedad and it has been elevated to the status of a Minor Basilica. The English name for La Piedad is Our Lady of Compassion.

Mary Hansen

.

VISIT OUR LADY OF LORETO – Baja California Peninsula

The town of Loreto is a magnet for its “perfect” climate (average temperature is in the 80’s) and vacation activities, along with its beaches. It is also known for its famous church: the mission Church of Our Lady of Loreto, the first mission church of the Californias.

An inscription above the main portal of the church solemnly declares its primacy: Cabeza y Madre de las Misiones  Baja y Alta California (“Head and Mother of the Missions of

Baja y Alta California (“Head and Mother of the Missions of

Lower and Upper California”). The mission is steps away from the shimmering, sapphire-blue waters of the Sea of Cortéz.

Loreto, “the oldest permanent settlement in all the Californias” is located on the eastern coast of the Baja California peninsula at the base of the Sierra de Gigante mountain range, 700 miles south of San Diego.

Loreto became the capital of Baja Sur and thus, was the first capital of the Californias.

The mission of Loreto has more claims to fame: It was the home of the Franciscan “Apostle of California” Fray Junípero Serra for a period of time. When the Jesuits were expelled from New Spain in 1767 the Franciscans were authorized to take over the 15 Jesuit-run missions on the Baja peninsula. Serra became Presidente of these missions in 1768 and the mission

of  Loreto served as his headquarters. Loreto was also the “cornerstone” and central departure point for missionary expansion northward into Alta California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, from which new missions and new towns and cities came into existence.

Loreto served as his headquarters. Loreto was also the “cornerstone” and central departure point for missionary expansion northward into Alta California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, from which new missions and new towns and cities came into existence.

The mission of Loreto was founded by Italian-born Jesuit and explorer Father Jean Marie de Salvatierra on Oct. 25, 1697. He dedicated the mission to Our Lady of Loreto for whom he had a keen devotion.(The tradition of Our Lady of Loreto commemorates the miraculous transference of the Holy House of Nazareth to the town of Loreto in Italy).

Father de Salvatierra disembarked at Baja, California, carrying the emblem of the cross and the statue of Our Lady of Loreto. He declared her queen of the expedition and Patroness of all future missions in California.

He brought his own life-sized statue of Our Lady of Loreto from Italy and described her reception by the new community: In a letter dated November 27, 1697, he wrote: “The next day we brought ashore the Holy Madonna. She was received on land with many salvos. We recited with the Indians the Ave Maria in their language and sang the litany of Loreto.

The Virgin was carried in procession, and the Indian men and women gave expression of their intense joy at the arrival of the sacred image—the tent donated by Don Domingo de la Canal was decorated as a church and on Saturday October 26 Mass was celebrated.”

The Virgin was carried in procession, and the Indian men and women gave expression of their intense joy at the arrival of the sacred image—the tent donated by Don Domingo de la Canal was decorated as a church and on Saturday October 26 Mass was celebrated.”

In 1697, the Jesuits were given authorization by the Spanish King to Christianize the Baja area. During the next 70 years they founded 14 more missions in the region. With the help of the local Guaycura Indians, construction on the first church of Loreto began in 1699. Jesuit Father Jaime Bravo initiated the building of a larger church in 1740.

The town of Loreto remained the capital and the commercial centre of the region for almost 150 years—until disaster struck in 1829: A devastating earthquake demolished much of the town. Although the church of Loreto was damaged, its basic structure, “solid, squat and simple,” remained intact.

In 1830 the capital was transferred to La Paz, a now-bustling city 210 miles south of Loreto. In 1854, diocesan clergy assumed control of the mission of Our Lady of Loreto. In 1967, Pope Paul Vl declared Our Lady the patrona principe of the Diocese of Mexicali.

A plaque in the narthex describes the church as a “magnificent temple with thick stone walls—worthy of the California capital.” Built in the shape of a Greek cross, it has a “very long rectangular floor plan somewhat out of proportion.”

The single nave, with its austere, white-washed interior and chestnut-brown cedar-beamed ceiling, is a cool and tranquil oasis from the blistering desert sun. The five-piece “very grandiose” gilded

altarpiece, however, is anything but austere: Painted in radiant shades of crimson red and powder blue, it is adorned with an array of 3-D sculpted cherubs, angels, grapes and scrolls.

altarpiece, however, is anything but austere: Painted in radiant shades of crimson red and powder blue, it is adorned with an array of 3-D sculpted cherubs, angels, grapes and scrolls.

A statue of Our Lady of Loreto with the Infant Christ stands at the center of the altarpiece, directly above the tabernacle. Fittingly, for a shrine of Loreto, a large painting above the altarpiece depicts the Holy Family in their home at Nazareth.

The first stone church is now a chapel, situated next to the presbytery. Dominating the space is the original statue of Our Lady of Loreto. The chapel’s ambiance—white-washed walls and an altarpiece in shades of robin’s-egg blue and cream—provides a soothing retreat for the weary soul.

The museum next door is a must-see: Its comprehensive “and surprisingly sophisticated” displays recount the history of the Baja and its missions. A plaque at the entrance movingly documents the gratitude of the people of Loreto toward the founding Jesuits: “To them we dedicate this museum as a humble and respectful recognition of their courage and greatness.”

In 1769, Blessed Serra departed from the mission of Loreto and journeyed to Alta California (present-day California) where he founded a series of new missions and settlements—with names like San Diego, San Francisco, Santa Barbara and Carmel.

But the mission of Our Lady of Loreto was the first of them all.

Mary Hansen writes from North Bay, Ontario

Reprinted with permission from the NATIONAL CATHOLIC REGISTER

OUR LADY OF ARANZAZU – Guadalajara, Jalisco

It’s easy to overlook the chapel of Our Lady of Aranzazu. You could walk right by it and not even give it a second glance. The facade is austere, stark, and utterly unassuming. But step inside and you enter a different world: a masterpiece of golden Churrigueresque architecture with an “astonishingly ornate” interior. “Divine” say some. “Stunning,” say others.

The word Churriguersque comes from a family of Spanish architects and artists, the Churriguera family. They developed an ultra-baroque, highly decorative architectural style—unique to Spain and Latin America, particularly Mexico—which was popular in the early 18 th century.

Residing over the main altar is the magnificent statue of Our Lady of Aranzazu who origina

tes from the Basque region of Northern Spain. A stone statue of her can be found in its own niche on the facade above the main entrance. And this is how she got her name: Centuries ago a young shepherd was tending his flock in the remote Basque mountainside. He suddenly “stumbled upon” a most unusual sight: an image of Our Lady and Child trapped in a thicket of thorns. “ Aranzazu!” “You are in the thorns!” shouted the startled shepherd. Word spread about the discovery and the Basque people soon adopted Our Lady of Aranzazu as their official Patroness. In time the devotion was brought to New Spain (Mexico) and a Franciscan church was built in her honour by Franciscan Padre F. Inigo Vallejo with the support of wealthy Basque settlers in Guadalajara.

tes from the Basque region of Northern Spain. A stone statue of her can be found in its own niche on the facade above the main entrance. And this is how she got her name: Centuries ago a young shepherd was tending his flock in the remote Basque mountainside. He suddenly “stumbled upon” a most unusual sight: an image of Our Lady and Child trapped in a thicket of thorns. “ Aranzazu!” “You are in the thorns!” shouted the startled shepherd. Word spread about the discovery and the Basque people soon adopted Our Lady of Aranzazu as their official Patroness. In time the devotion was brought to New Spain (Mexico) and a Franciscan church was built in her honour by Franciscan Padre F. Inigo Vallejo with the support of wealthy Basque settlers in Guadalajara.

At one time the chapel was part of a vast Franciscan monastery which was several city-blocks in size. The complex consisted of the principal Franciscan church (across the road from the chapel), six chapels, a convent, a graveyard, an orchard and a huge atrium (courtyard). By 1750 the monastery’s vast motherhouse housed as many as 100 friars. It was the centre of Franciscan evangelization efforts in Western Mexico. Only two structures remain from this era, the church of San Francisco and the chapel of Our Lady of Aranzazu which was built between 1749 and 1752.

At one time the chapel was part of a vast Franciscan monastery which was several city-blocks in size. The complex consisted of the principal Franciscan church (across the road from the chapel), six chapels, a convent, a graveyard, an orchard and a huge atrium (courtyard). By 1750 the monastery’s vast motherhouse housed as many as 100 friars. It was the centre of Franciscan evangelization efforts in Western Mexico. Only two structures remain from this era, the church of San Francisco and the chapel of Our Lady of Aranzazu which was built between 1749 and 1752.

The chapel consists of one narrow nave (there used to be three) and three gilded Churriqueresque altarpieces, extravagantly adorned with wooden statues, carvings and over-sized canvas paintings.

The church was declared a national monument in 1932, a “patrimonial legacy” which had been preserved for centuries. During Mexico’s wars of Reform in the 1920’s, the church —which was used as military quarters—suffered extensive damage.

The chapel of Our Lady of Aranzazu has been described in travel books as a “splendid Baroque jewel.” An apt description. A short walk from the zocalo (the city centre), it is a must-see for any visitors to the city.

Written by Mary Hansen