MEXICAN MARTYRS

THE PRIEST MARTYRS DURING THE PERSECUTION OF THE CHURCH IN MEXICO IN THE 1920’S

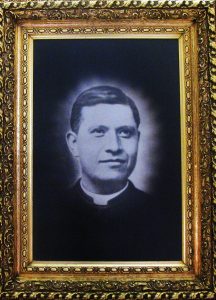

The above photo is of San Pedro Esqueda Ramirez (1887-1927): He was born in the diocese of San Juan de Los Lagos, in the state of Jalisco. He was an Apostle of Eucharistic Adoration and of the Blessed Virgin Mary. He was particularly devoted to the catechesis of children. He was shot three times on Nov. 22, 1927 at the age of 40. He was canonized by St. Pope John Paul II on May 21, 2000.

“Garrido, the governor of Tabasco, had destroyed every church.” “He had organized a militia of Red shirts (his private army of 6,000 young men) in his hunt for a church or a priest. Private houses were searched for religious items and prison was the penalty for possessing them. Every priest was hunted down and shot…”

Thus wrote British writer Graham Greene (an atheist until his conversion to the Catholic church at the age of 22) in his non-fiction travel book The Lawless Roads. “In Tabasco there was no priest left and no church standing except one now used as a school,” he was told by a Tarascan woman. “But what happens when you die?” questioned Greene. “Oh” she said, “we die like dogs.” No religious ceremony was allowed at the grave.

In his book Greene speaks of a land of “ruined churches” and “headless statues.” “In Chiapas the churches still stand, shuttered and ruined and empty but they fester—the whole village festers.” He tells of villagers weeping while their churches are being desecrated: “The statues were carried out of the church while the inhabitants watched, sheepishly, and saw their own children encouraged to chop up the images, in return for little presents of candy.” It was commonplace (according to Greene’s biographer, Norman Sherry) to see animals displayed in church sanctuaries: a pig would be called the pope, a cow would be called Our Lady of Guadalupe and a donkey would be named Christ. He also stated that the aforementioned governor of Tabasco “replaced the worship of God with the worship of the Yucca plant.” It is interesting to note that he called one of his sons, Lenin.

And what happened to Catholic education during this period? Article 3 of the 1917 constitution secularized all education: religious education was forbidden in both private and public schools. One clause in the article stipulates: “The education imparted by the state shall be a socialist one.” Further along we read: “No one connected with any religious society shall be allowed to teach or assist the schools financially.”

Francis F. Kelley, Bishop of Oklahoma and Tulsa, discusses the matter of education in his aptly named book Blood Drenched Altars. He revealed the oath that teachers in the state of Yucatan were forced to sign: “I solemnly declare myself an atheist, an irreconcilable enemy of the Roman, Apostolic, Catholic religion and I will exert my efforts to fight against the clergy in whatever field may be necessary—and take a leading part in attacking the Roman, Apostolic, Catholic religion wherever it manifests itself”—and lastly, “I will not permit any member of my household to take part in any religious act whatsoever.”

Not all teachers complied: many refused to cooperate with the authorities. In the city of Aguascalientes, for example, all resigned. In the state of Michoacan “60 public school teachers resigned rather than teach as prescribed.”

Was this Russia at the height of the Stalinist years? Or Spain in the depths of the Civil War? Or Romania under the Communist dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu?

It was none of these. It was Mexico in the early part of the 20th century. According to Robert Royal, in his book Martyrs of the Twentieth Century, after the imposition of its radical 1917 constitution, Mexico became one of three Communist countries in the last century (including Soviet Russia and Republican Spain) whose singular purpose was the eradication of the Christian religion. Author Evelyn Waugh, another British convert, noted that “the legal position of the church in Mexico has no parallel in any country except Soviet Russia” (namely, that it was completely illegal).

The persecution of the Catholic church in Mexico intensified exponentially when Plutarco Calles (an avowed Mason) came to power in 1924. Although there was sporadic hatred displayed against the church throughout the previous century, it was minor compared to the “persecution brutale” of the 1920’s.

Pope Pius XI, the reigning pope of the time (1922-1939) wrote an encyclical in 1926 titled Iniquis Afflictisque which deplored the barbarities committed against the church in Calles’ Mexico, “cruelties and atrocities scarcely credible in the 20th century.” He stated that the persecutions in Mexico “exceeded the most bloody persecutions of the Roman emperors.”

The most famous of the Mexican priest martyrs was the Jesuit priest Father Miguel Pro who wrote, “From all sides we receive news of attacks and the victims are many; the number of martyrs grows each day.” In the first week of May 1926, alone, there was a mass execution of seventeen priests in Mexico City. During the four years of his presidency Calles oversaw the execution of ninety priests without trial. According to Saints and Sinners in the Cristero War, fanatical atheist Calles once told a French diplomat, Ernest Lagarde, that “it was time to finish with the church and to rid the country of it once and for all.” He certainly did his best to achieve this goal. In 2000 St. Pope John Paul ll canonized 24 Mexican martyrs. Twenty three of them were priests.

During the years between 1926 and 1929 scores of priests and laymen were executed, religious orders and vows were forbidden and priests were not allowed to say Mass. They could be executed for administering the sacraments. Article 24 of the Constitution decreed that all religious worship must be regulated by the State. Churches were closed (although a few were left open) but no priest was allowed to enter. A priest was not even allowed to say a prayer over a dying Mexican soldier. Such acts were considered criminal and punishable by law. In 1925 a law was passed stating that priests must marry and must have studied in official (i.e. “anti-religious” schools). The Constitution denied legal status to any religion. Marriage was declared solely a civil contract. The list is a long one. Church property was confiscated on a widespread scale.

In 1926, with the assent of the Holy See, the bishops of Mexico took unprecedented and extraordinary measures to protect the Eucharist from sacrilegious government control: they ordered that the Blessed Sacrament be removed from all the churches in the country. Thus Masses were no longer celebrated in the churches of Mexico.

But—there were Masses, the Sacraments were distributed—clandestinely. Masses were held in “underground churches,” in private homes, in garages, in forests. Secret Masses were held all over the country. Confessions were heard. The Sacrament of the Sick was being administered. On one First Friday Father Miguel Pro (wearing different disguises) distributed 1,200 Communions; his normal daily distribution was never less than 300. All at the risk of his life. And those offering their homes for such Masses. Father Pro had offered his life for the Church in Mexico. He was shot by a firing squad on November 23, 1927.

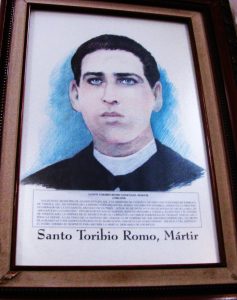

Throughout this severe persecution the clergy were heroic. Magnificent. One young priest, 28-year-old Father Toribio Romo Gonzalez, prayed, “Lord, I offer my blood for the peace of the Church.” He was murdered later that night. These words were spoken by the soldiers: “This is the priest. Let us kill him.”

Father David Uribe Velacco was martyred at the age of 39 on April 2, 1927. In prison he wrote the following: “What joy it is to die defending the rights of God! I am in your hands O Lord and in those of Our Lady of Guadalupe.”

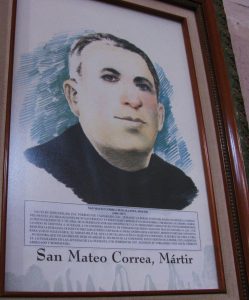

Father Mateo Correa Magallanes was ordered to reveal the sins of several confessions he had heard. “I will shoot you if you don’t tell me!” shouted the revolutionary to Father Matteo with a gun pointed at the priest’s head. “Never! I would rather die first!” he said. “Then you will die!” screamed his opponent. Father Correa was executed on Feb. 6, 1927.

Father Miguel de la Mora, pastor of the cathedral in Colima, Jalisco (he was “full of the love for the poor”), decided to remain with his parishioners when all priests were expelled from the area. He was shot while praying the Rosary.

The Mexican laypeople were equally courageous. More than 20,000 people joined the funeral cortege for Father Pro in Mexico City, risking their lives in the process. Shouts resounded through the procession:

“Viva Cristo Rey! Long live the martyrs! Long live the pope! Long live our bishops! Long live our priests!”

“Lord, if you wish martyrs, here is our blood, here are our lives.”