STORY FOR AUGUST 2024

THE CATHEDRAL OF ZACATECAS, Zac.

This is considered one of the most beautiful churches in the country.

SOME OF MY FAVOURITE SHRINES IN MEXICO

MEXICAN MARTYRS: The Brave Lay Martyrs of Mexico

MEXICAN MARTYRS

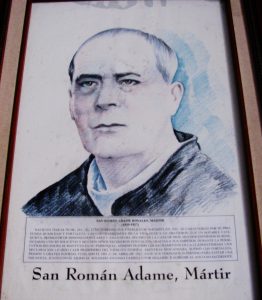

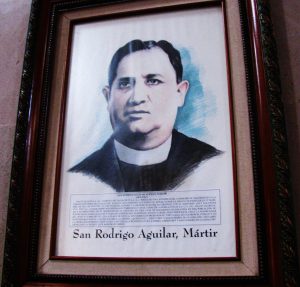

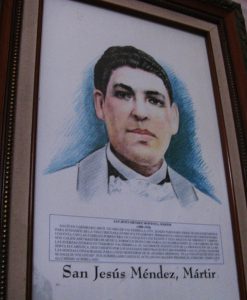

THE PRIEST MARTYRS DURING THE PERSECUTION OF THE CHURCH IN MEXICO IN THE 1920’S

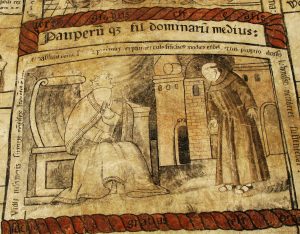

The above photo is of San Pedro Esqueda Ramirez (1887-1927): He was born in the diocese of San Juan de Los Lagos, in the state of Jalisco. He was an Apostle of Eucharistic Adoration and of the Blessed Virgin Mary. He was particularly devoted to the catechesis of children. He was shot three times on Nov. 22, 1927 at the age of 40. He was canonized by St. Pope John Paul II on May 21, 2000.

“Garrido, the governor of Tabasco, had destroyed every church.” “He had organized a militia of Red shirts (his private army of 6,000 young men) in his hunt for a church or a priest. Private houses were searched for religious items and prison was the penalty for possessing them. Every priest was hunted down and shot…”

Thus wrote British writer Graham Greene (an atheist until his conversion to the Catholic church at the age of 22) in his non-fiction travel book The Lawless Roads. “In Tabasco there was no priest left and no church standing except one now used as a school,” he was told by a Tarascan woman. “But what happens when you die?” questioned Greene. “Oh” she said, “we die like dogs.” No religious ceremony was allowed at the grave.

In his book Greene speaks of a land of “ruined churches” and “headless statues.” “In Chiapas the churches still stand, shuttered and ruined and empty but they fester—the whole village festers.” He tells of villagers weeping while their churches are being desecrated: “The statues were carried out of the church while the inhabitants watched, sheepishly, and saw their own children encouraged to chop up the images, in return for little presents of candy.” It was commonplace (according to Greene’s biographer, Norman Sherry) to see animals displayed in church sanctuaries: a pig would be called the pope, a cow would be called Our Lady of Guadalupe and a donkey would be named Christ. He also stated that the aforementioned governor of Tabasco “replaced the worship of God with the worship of the Yucca plant.” It is interesting to note that he called one of his sons, Lenin.

And what happened to Catholic education during this period? Article 3 of the 1917 constitution secularized all education: religious education was forbidden in both private and public schools. One clause in the article stipulates: “The education imparted by the state shall be a socialist one.” Further along we read: “No one connected with any religious society shall be allowed to teach or assist the schools financially.”

Francis F. Kelley, Bishop of Oklahoma and Tulsa, discusses the matter of education in his aptly named book Blood Drenched Altars. He revealed the oath that teachers in the state of Yucatan were forced to sign: “I solemnly declare myself an atheist, an irreconcilable enemy of the Roman, Apostolic, Catholic religion and I will exert my efforts to fight against the clergy in whatever field may be necessary—and take a leading part in attacking the Roman, Apostolic, Catholic religion wherever it manifests itself”—and lastly, “I will not permit any member of my household to take part in any religious act whatsoever.”

Not all teachers complied: many refused to cooperate with the authorities. In the city of Aguascalientes, for example, all resigned. In the state of Michoacan “60 public school teachers resigned rather than teach as prescribed.”

Was this Russia at the height of the Stalinist years? Or Spain in the depths of the Civil War? Or Romania under the Communist dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu?

It was none of these. It was Mexico in the early part of the 20th century. According to Robert Royal, in his book Martyrs of the Twentieth Century, after the imposition of its radical 1917 constitution, Mexico became one of three Communist countries in the last century (including Soviet Russia and Republican Spain) whose singular purpose was the eradication of the Christian religion. Author Evelyn Waugh, another British convert, noted that “the legal position of the church in Mexico has no parallel in any country except Soviet Russia” (namely, that it was completely illegal).

The persecution of the Catholic church in Mexico intensified exponentially when Plutarco Calles (an avowed Mason) came to power in 1924. Although there was sporadic hatred displayed against the church throughout the previous century, it was minor compared to the “persecution brutale” of the 1920’s.

Pope Pius XI, the reigning pope of the time (1922-1939) wrote an encyclical in 1926 titled Iniquis Afflictisque which deplored the barbarities committed against the church in Calles’ Mexico, “cruelties and atrocities scarcely credible in the 20th century.” He stated that the persecutions in Mexico “exceeded the most bloody persecutions of the Roman emperors.”

The most famous of the Mexican priest martyrs was the Jesuit priest Father Miguel Pro who wrote, “From all sides we receive news of attacks and the victims are many; the number of martyrs grows each day.” In the first week of May 1926, alone, there was a mass execution of seventeen priests in Mexico City. During the four years of his presidency Calles oversaw the execution of ninety priests without trial. According to Saints and Sinners in the Cristero War, fanatical atheist Calles once told a French diplomat, Ernest Lagarde, that “it was time to finish with the church and to rid the country of it once and for all.” He certainly did his best to achieve this goal. In 2000 St. Pope John Paul ll canonized 24 Mexican martyrs. Twenty three of them were priests.

During the years between 1926 and 1929 scores of priests and laymen were executed, religious orders and vows were forbidden and priests were not allowed to say Mass. They could be executed for administering the sacraments. Article 24 of the Constitution decreed that all religious worship must be regulated by the State. Churches were closed (although a few were left open) but no priest was allowed to enter. A priest was not even allowed to say a prayer over a dying Mexican soldier. Such acts were considered criminal and punishable by law. In 1925 a law was passed stating that priests must marry and must have studied in official (i.e. “anti-religious” schools). The Constitution denied legal status to any religion. Marriage was declared solely a civil contract. The list is a long one. Church property was confiscated on a widespread scale.

In 1926, with the assent of the Holy See, the bishops of Mexico took unprecedented and extraordinary measures to protect the Eucharist from sacrilegious government control: they ordered that the Blessed Sacrament be removed from all the churches in the country. Thus Masses were no longer celebrated in the churches of Mexico.

But—there were Masses, the Sacraments were distributed—clandestinely. Masses were held in “underground churches,” in private homes, in garages, in forests. Secret Masses were held all over the country. Confessions were heard. The Sacrament of the Sick was being administered. On one First Friday Father Miguel Pro (wearing different disguises) distributed 1,200 Communions; his normal daily distribution was never less than 300. All at the risk of his life. And those offering their homes for such Masses. Father Pro had offered his life for the Church in Mexico. He was shot by a firing squad on November 23, 1927.

Throughout this severe persecution the clergy were heroic. Magnificent. One young priest, 28-year-old Father Toribio Romo Gonzalez, prayed, “Lord, I offer my blood for the peace of the Church.” He was murdered later that night. These words were spoken by the soldiers: “This is the priest. Let us kill him.”

Father David Uribe Velacco was martyred at the age of 39 on April 2, 1927. In prison he wrote the following: “What joy it is to die defending the rights of God! I am in your hands O Lord and in those of Our Lady of Guadalupe.”

Father Mateo Correa Magallanes was ordered to reveal the sins of several confessions he had heard. “I will shoot you if you don’t tell me!” shouted the revolutionary to Father Matteo with a gun pointed at the priest’s head. “Never! I would rather die first!” he said. “Then you will die!” screamed his opponent. Father Correa was executed on Feb. 6, 1927.

Father Miguel de la Mora, pastor of the cathedral in Colima, Jalisco (he was “full of the love for the poor”), decided to remain with his parishioners when all priests were expelled from the area. He was shot while praying the Rosary.

The Mexican laypeople were equally courageous. More than 20,000 people joined the funeral cortege for Father Pro in Mexico City, risking their lives in the process. Shouts resounded through the procession:

“Viva Cristo Rey! Long live the martyrs! Long live the pope! Long live our bishops! Long live our priests!”

“Lord, if you wish martyrs, here is our blood, here are our lives.”

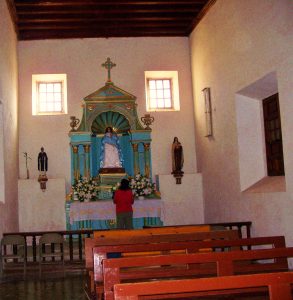

OUR LADY OF LORETO, Baja California, Mexico

The town of Loreto, is a magnet for its “perfect” climate” (average temperature is in the 80’s) and vacation activities, along with its beaches.

It is also known for its famous church: the mission church of Our Lady of Loreto, the first mission church of the Californias.

An inscription above the main portal of the church solemnly declares its primacy: Cabez y Madre de las Misiones Baja y Alta California (Head and Mother of the Missions of Lower and Upper California). The mission is steps away from the shimmering, sapphire-blue waters of the Sea of Cortez.

Loreto, “the oldest permanent settlement in all the Californias” is located on the eastern coast of the Baja California peninsula at the base of the Sierra de Gigante mountain range, 700 miles south of San Diego.

Loreto became the capital of Baja Sur and thus was the first capital of the Californias.

The mission of Loreto has more claims to fame: It was the home of the Franciscan “Apostle of California,” Junipero Serra, for a period of time. When the Jesuits were expelled from New Spain in 1767, the Franciscans were authorized to take over the 15 Jesuit-run missions on the Baja peninsula. Serra became president of these missions in 1768 and the mission of Loreto served as his headquarters. Loreto was also the “cornerstone” and central departure point for missionary expansion northward into Alta California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, from which new missions and new towns and cities came into existence.

The mission of Loreto was founded by Italian-born Jesuit and explorer Father Jean Marie de Salvatierra on Oct. 25, 1697. He dedicated the mission to Our Lady of Loreto, for whom he had a keen devotion. (The tradition of Our Lady of Loreto commemorates the miraculous transference of the Holy House of Nazareth to the town of Loreto in Italy). Father de Salvatierra disembarked at Baja, carrying the emblem of the cross and the statue of Our Lady of Loreto. He declared her the queen of the expedition and patroness of all future missions in California.

He brought his own statue of Our Lady of Loreto from Italy and described her reception by the new community: In a letter dated Nov. 27, 1697, he wrote, “The next day we brought ashore the Holy Madonna. She was received on land with many salvos. We recited with the Indians the Ave Maria in their language and sang the Litany of Loreto. The Virgin was carried in procession and the Indian men and women gave expression of their intense joy at the arrival of the sacred image. The tent donated by Don Domingo de la Canal was decorated as a church, and, on Saturday, Oct 26, Mass was celebrated.”

In 1697 the Jesuits were given authorization by the Spanish king to Christianize the Baja area. During the next 70 years, they founded 14 more missions in the region. With the help of the local Guaycura Indians, construction on the first church of Loreto began in 1699. Jesuit Father Jaime Bravo initiated the building of a larger church in 1740. In 1854 diocesan clergy assumed control of the mission. In 1967 Pope Paul VI declared Our Lady of Loreto the patrona principe of the diocese of Mexicali.

A plaque in the temple describes the church as “a magnificent temple with thick stone walls.” The single nave with its austere, white-washed interior is a cool and tranquil oasis from the blistering desert sun. The five-piece “very grandiose” gilded altarpiece, however, is anything but austere: Painted in radiant shades of crimson red and powder blue, it is adorned with an array of 3-D sculpted cherubs, angels, grapes and scrolls.

A statue of Our Lady of Loreto with the Infant Christ stands at the center of the altarpiece, directly above the tabernacle. Fittingly, for a shrine of Loreto, a large painting above the altarpiece depicts the Holy Family in their home at Nazareth.

A plaque at the entrance of the church’s museum documents the gratitude of the people of Loreto toward the founding Jesuits: “To them we dedicate this museum as a humble and respectful recognition of their courage and greatness.”

In 1769 St. Serra departed from the mission of Loreto and journeyed to Alta California (present-day California) where he founded a series of new missions and settlements—with names like San Diego, San Francisco, Santa Barbara and Carmel.

But this mission of Our Lady of Loreto was the first of them all.

Mary Hansen

This article was reprinted with permission from the NATIONAL CATHOLIC REGISTER.

PLEASE NOTE: THE NAME OF THIS WEBSITE HAS BEEN CHANGED TO:

mexicanmadonnas.com

ST. JUAN DIEGO’S FIRST CHURCH, Tlaltelolco, Mexico City

In 1518, a typical day in Tlaltelolco in the Aztec empire saw thousands of people milling about, trading, selling, bartering and buying. The town’s bustling marketplace was the largest in the sprawling empire. At the hub of all this activity stood the massive temple and its twin pyramids dedicated to the pagan gods, Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. The emperor, Montezuma ll, presided over this vast domain. But not for much longer.

Within three years, life for the Aztecs would be radically altered: Tlaltelolco would become a Christian stronghold and a church would be built on the site of the pagan temple.

This church, named after St. James, the Apostle, the patron of Spain, would be the place where Juan Diego, the most renowned visionary in the Americas, would be baptized and receive catechetical instructions.

He would be headed here on that momentous Saturday morning of December 9, 1531, when he would encounter Our Lady of Guadalupe for the first time.

Ten years earlier, in 1521, the course of Mexican history changed forever. That was the year that the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez, defeated the last Aztec emperor, Cuauhtemoc, at Tlaltelolco in the final battle for the conquest of Mexico. Montezuma had died a year earlier. A plaque at the site poignantly tells of the battle: “On Aug. 13, 1521, heroically defended by Cuauhtemoc, Tlaltelolco fell to Hernan Cortez. It was neither a triumph nor a defeat but the birth of the mestizo nation that is the Mexico of today.”

In 1524, the first band of missionaries, twelve Franciscans—popularly called “the twelve apostles”—landed in New Spain (Mexico) for the first time and organized a center of evangelization at Tlaltelolco. Juan Diego, along with his wife (who died in 1529) and uncle, were among the first Christians in the newly conquered country. They were baptized in 1525. Juan Diego was a disciple of one of these “twelve,” Fray Torobio Paredes de Benavente, who was renowned for his humility and saintliness

A Franciscan convent was founded at Tlaltelolco in 1535 and the Church of St. James was built in 1543. Bernal Diaz, a soldier who fought alongside Cortes in the battle for Mexico, speaks of this church in his acclaimed account, The Conquest of New Spain: “After we conquered the great and strong city (Tlaltelolco) we decided to build a church to our patron and guide, St. James, in place of that of Huichilobos’ cue (temple)—and a great part of the site was taken for this purpose.”

Diaz described the frightening image of Huichilobos, which he saw on an altar: It was “giant-sized” with a “very broad face and huge terrible eyes.” Another image he described was that of Tezcatlipoca, the god of hell—it was surrounded by figures of devils with snakes’ tails.”

Not only was the church built on the site of the razed temple, it was built with the very stones of the razed temple. This was a common practice in the building of the earliest colonial churches in New Spain. Its purpose was twofold: to signify that the Christian religion is the one true religion and supplants the former pagan religion. The excavated ruins of the temple and pyramids—they are mammoth—are visible today. “The pyramids were the height of a skyscraper,” reports one historian.

The gargantuan, “fortress-like” Church of St. James is typical of the austere style of 16th century Franciscan architecture. The interior follows suit: The ultramodern interior of the single nave church is characterized by a stark and unadorned simplicity. Directly inside the central (west) doors of the church is the baptismal font in which Juan Diego was baptized. Nearby is a life-size statue of Juan Diego kneeling in front of a painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe. He is displaying his tilma (cloak) which holds an array of three-dimensional, petal-pink Castilian roses. The drama is of Guadalupe is about to begin!

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN:

Adjoining the church is the vermilion-red Franciscan convent of the Holy Cross, the place where Juan Diego attended weekly catechism classes and Saturday Masses in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The miraculous appearance of the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe on Juan Diego’s tilma occurred on Dec. 12, 1531. He spent the rest of his life as protector of the blessed image, living in the hermitage, the first church built to house the miraculous painting. Until his death in 1548, he devoted his days to prayer, contemplation and evangelization. Today the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe is the most visited shrine in the world, with 20 million pilgrims a year. Juan Diego was canonized by Pope John Paul ll in 2002. An astonishing 12 million people lined the streets of Mexico City to welcome the Pope as he arrived for the ceremony. And to think—it all began here in the Church of St. James in Tlatelolco.

Mary Hansen

RERINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC REGISTER.

The name of this website has been changed to mexicanmadonnas.com

LA MACANA, CHURCH OF ST. FRANCIS, Mexico City

The statue of Our Lady of Macana was brought from Toledo, Spain, by Franciscan missionaries in 1596. She is much loved and venerated by the people of Mexico City where she finds her home in the Church of San Francisco in the historical area of the city. The small image (it is about 20” in height) is placed in a prominent position in the church on a side wall near the main altar. She is known for her many miracles of healing. One such famous one is the curing of a ten-year-old child of paralysis in 1961.

The church of San Francisco is the oldest in the city and was founded by the “Twelve Apostles,” the first 12 Franciscan friars who arrived in 1524 to bring the faith to the newly conquered territory of New Spain. Their leader was the saintly Fray Martin de Valencia. This church was known as the “Mother” Church of all the Franciscan churches in continental America.

All went well until Aug. 10, 1680. On that day an insurrection arose because of the abuses by some of the Spanish laypeople (not on the part of the clergy, however) toward the indigenous people and several soldiers and missionaries were killed. Even Our Lady of Macana suffered from several golpes (hits) to her face. The friars, in time, restored the famous statue and she was placed at another convent where she resided until Jan. 26, 1755. During the first persecutions of the church in Mexico the Franciscans were expelled from their convent in 1861 and took the statue with them for safe-keeping. She was hidden away in several locations during this time. She was returned to her home at San Francisco in Mexico City in 1949.

The visitor to San Francisco will notice a number of “ex-votos” near the statue of La Macana. These are small drawings or photos from grateful recipients to thank Our Lady of Macana for her blessings and miracles. This is not surprising: She is, after all, known as Our Lady of Miracles!

THE CATHEDRAL OF THE ASSUMPTION, Cuernavaca, Morelos

In 1957 workmen were busy renovating the interior of the 16th century Cathedral of Cuernavaca and were astounded by what they found in the walls of the nave: Under layers of dirt, grime and whitewash they discovered artistic treasures—frescoes from the 1600’s were glimpsed on the original walls of the church. As the renovation progressed “the scale and extent of the murals astounded the excited researchers.” This caused a sensation in the country!

What did the murals depict? The “magnificent” murals told the story of twenty-six martyrs, crucified in Japan, one of whom was the Mexican-born Franciscan Brother Philip of Jesus. HIS STORY IS TOLD IN THE NOVEMBER 2023 ARCHIVES ON THIS WEBSITE.

The astonishing revelation of the murals created “almost a national shrine to San Felipe” who was Mexico’s first saint and martyr. And you would have to ask: “How did the young Franciscan find himself in Japan?”

In October 1596 San Felipe was on a Spanish galleon which was sailing from Manila, bound for Acapulco. San Felipe had just finished his seminary training in the Philippines and was enroute to Mexico to be ordained for the priesthood. He never made it. His ship ran into a typhoon and the unfortunate passengers were catapulted onto the coast of Japan. The friars and several laypeople aboard were taken prisoner and condemned by the overlords as “spies and heretics.” They were condemned to death by crucifixion.

The enormous frescoes (almost 75 ft. long and 25 ft. high) were painted between 1628 and 1697. They depicted the death of the martyrs in harrowing detail: Says one author, “we see his (San Felipe) arrival on the shores of Japan, the journey by boat and cart to the place of execution and finally his crucifixion.”

In 1529 the first friars arrived in Cuernavaca and established their monastery. It is not surprising that Franciscans were the first to evangelize the area. The Spanish conqueror, Cortez, was so impressed by the holiness and ascetisicm of the Fransiscan order that, after his conquest of the Aztecs in 1521, he entrusted the evangelization of the new country to them.

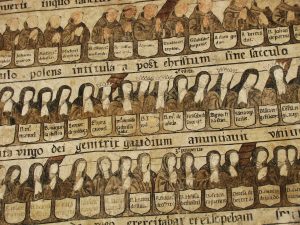

Construction of the church began in 1529 and was completed in 1552. Traces of the Franciscan Order can be found throughout the church. More frescoes can be found on the walls of the cloister: “The best preserved of these is the delightful lineage of St. Francis—Rows and rows of diminutive nuns and friars, each holding a name plaque.” Other frescoes in the cloister display events from the life of St. Francis. The skull and crossbones, symbol of the Order, can be found overlooking the main entrance to the cathedral.

Adjacent to the cathedral is the castle which Cortez built for his Spanish-born bride. Its size is overwhelming! It makes a first-spot for tourists to visit when they arrive in the city. But the Cathedral of the Assumption in Cuernavaca is the very next step on every tourist’s destination! It is hard to miss—its glorious tower overlooks the entire city.

PLEASE NOTE!

The name of this website has been changed to

mexicanmadonnas.com

THE NAME OF THIS WEBSITE HAS BEEN CHANGED TO:

mexicanmadonnas.com

SAN FELIPE DE JESUS, Mexico City—MEXICO’S FIRST SAINT

On May 13, 1524, twelve Franciscan friars from Spain set foot on Mexican soil for the first time. The evangelization of Mexico had begun!

According to Robert Ricard in The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico, this “sweeping wave of evangelization was one of the great glories of the 16th century.” “Missions sprang up everywhere” he said.

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs in 1521 the Franciscan Order was chosen to bring the Catholic faith to the new lands. “They were the kingpins of the young Mexican church!” said Ricard. Dominicans, Augustinians, and Jesuits would follow. But the Franciscans were the first.

Cortez chose this Order because of the exemplary holiness of their lives. Historians spoke of the “eminent virtues” of so many of the founders of the church in New Spain. In 1545 Bishop Juan de Zumarraga wrote about the “extreme humbleness of the Franciscan convent in Mexico City.” “The religious there lived in the greatest poverty,” he said. He recalled that the Indians marvelled at the friars, especially—“at their scorn of the gold and silver to which the Spanish laymen gave such value.”

Is it any wonder that so many Indians converted to the Christian faith? The Aztecs embraced human sacrifice on a horrific scale. At the inauguration of the temple of Tlaltelolco in 1487, for example, 20,000 warriors were sacrificed on its altars at the command of the Aztec emperor. The serpent-god Huitzilopochtli was insatiable in his demands for such sacrifice.

After the miraculous appearance of Our Lady of Guadalulpe in 1531 at Tepeyac Hill in Mexico City human sacrifice was abolished in the country. Conversions to the faith on a scale “perhaps unprecedented in human history” occurred. Within a decade more than nine million Aztecs became Christian. “Churches, monasteries, convents, hospitals, schools, and workshops sprang up all over the country in the wake of this phenomenal missionary conquest.” For who could resist this message of maternal love from Our Lady? “I am your merciful Mother—Am I not here who am your Mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection? Is there anything else you need?” Furthermore, she appeared as La Morenita, the dark-skinned one. She was one of them!

This was the vibrant religious atmosphere that surrounded the pious new arrivals from Spain, Alonso de las Casas and Antonia Ruiz Martinez. They were just a young couple when they travelled from Salamanca in October of 1571. They marvelled at the splendour and magnificence of Mexico City. Alonso was talented and enterprising and realized that he had come to a land of opportunity. On May 1, 1572, the first of their children was born. He was baptized in the great Cathedral of Mexico City. They named him Felipe.

Each year the fortunes of the father grew exponentially. “This is the best place in the world to be!” enthused Alonso. This affluence affected the boy. He became proud of his opulent wardrobe, of his spirited horses! And Felipe became more irresponsible and restless by the day. Only the tears of his mother moved him. “Felipillo!” she implored, “Become a saint!”

The boy had other ideas, however. When he was 13 his father took him to the port of Acapulco. He was thrilled to see so many merchant ships from the exotic Orient: from Japan! China! The Philippines! He loved listening to the “fabulous” stories of the sailors best of all. “Oh, the places I will go!” he thought. How he dreamed!

To everyone’s surprise, however, the teenager had a sudden change of heart: “I want to become a friar!” he said. With that in mind he arrived at the Reformed Franciscan Convent of Santa Barbara in Puebla. Sadly, his zeal did not last. After a few months he left the Order and embarked on a merchant career. In 1591 his wealthy father gave him a substantial amount of money to set sail for the Philippines to embark upon a business venture. In Manila he led a most hedonistic lifestyle. One far, far from God.

Our Lord intervened, however; While there his heart was deeply touched to the core, and, “Sobbing and repentant,” he joined the Franciscan friary of Santa Maria de los Angeles in Manila under the direction of Novice Master friar Vincent Valero. The 21-year-old was admitted to the friary on May 21, 1593. He had chosen a particularly severe Order, a group of discalced friars who “embraced strictness in dress, work and prayer.” A Franciscan friary in the Philippines? Yes: In 1576 King Philip ll of Spain appointed the Franciscan Order to be the evangelizers of the country.

After several years of seminary formation his superiors decided he was ready for ordination. There was only one problem: There was no bishop in the country at the time! Thus it was that the Franciscan superiors made the fateful decision to send him back to Mexico for his ordination.

On July 12, 1596, he and several friars left Manila and set sail on the Spanish galleon (ironically called San Felipe) for Acapulco, Mexico. The ship was blown off course by a typhoon and was shipwrecked off the coast of Japan. San Felipe and his Franciscan companions were taken prisoner.

Japan! Only a few years earlier, in 1549, Jesuit priest St. Francis Xavier and two other Jesuits waded ashore onto the Japanese coast. They were the first missionaries in the country and met with extraordinary success. Nearly half a million Buddhists converted to the Catholic faith.

Circumstances changed later for all Catholics in the country, however: In 1597 the Catholic faith was banned and all religious in Osaka and Kyoto were to be rounded up and killed. A total of twenty-six Catholics would soon be crucified and martyred for their faith. They would become known as the Twenty-Six Martyrs of Nagasaki. One hundred and thirty Catholic churches would be burned as well.

San Felipe was one of these martyrs. He and the others were tortured and mutilated (their ears and noses were cut off) and were paraded in oxcarts through the cities of Kyoto, Osaka and Sakai. Father Paul Miki, S.J., one of the best known of these martyrs, and considered to be the most eloquent preacher in Japan, preached passionately during his via crucis. The three youngest catechists (the youngest was only twelve) kept singing out the Our Father and the Hail Mary.

On Jan. 9, the martyrs began their brutal forced march (a journey of 27 days) to the city of Nagasaki where their crosses awaited them. The road to Nagasaki was lined with Christians who joined in with the martyrs in praising God and singing hymns. There were many eyewitnesses to the shocking events. As the crucifixions began, both the martyrs and the crowd began chanting Jesus! Maria! Jesus! Maria! Jesus! Maria! The date was Feb. 5, 1597.

When it was San Felipe’s turn he clasped his cross and cried out in a loud voice:

“O happy ship! O happy galleon for Philip! Lost for my gain—no loss for me but the greatest of all gain!” All the while repeating the holy name of Jesus.

During the savage Cristero War in Mexico (1926-1929) it is said that every Cristero soldier carried a picture of San Felipe close to his heart. He was their very own hero. He was one of them! And they recognized, of course, that they and San Felipe were both fighting against the same enemy.

EPILOGUE:

In the 1950’s San Felipe came to prominence once more in the country and in the most surprising manner: the year was 1957. Workmen were busy renovating the interior of the 16th century Cathedral of Cuernavaca when they came across something astonishing: Under layers of dirt, grime and whitewash they discovered artistic treasures—frescoes from the 1600’s, painted on the original walls of the church. As the renovation progressed “the scale and extent of the murals astounded the excited researchers.” This caused a sensation in the country.

What did these “magnificent” murals depict? They told the story of the twenty-six martyrs of Japan. The revelation created “almost a national shrine to San Felipe.” The enormous frescoes—almost 75 ft. long and 25 ft. high—were painted between 1628 and 1697. They depicted the death of the martyrs in harrowing detail. Says one author: “We see San Felipe’s arrival on the shores of Japan, the journey by boat and cart to the place of execution and finally his crucifixion.”

Felipe was beatified on Sept. 14, 1627 and canonized on June 8, 1862 by Pope Pius IX. A temple was built in his honour in 1886 in the historical centre of Mexico City. He is the city’s official patron.

His feast day is Feb. 5.

PLEASE NOTE!!!

The name of this website has been changed to mexicanmadonnas.com

This article has been reprinted with permission from ONE PETER FIVE.

l